(This event propelled me to write "Diagnosing No-Starts on Some 740/940 Volvos.")

I was chasing red herrings here! |

One December, our 1987 740 Turbo Volvo station wagon died. Its death was a great mystery. What killed it? As a physicist turned writer, I wondered if I could solve this puzzle. Money played a major part, of course, since professional mechanics cost an arm and a leg. I had diagnosed no-starts before, but this journey would test me as a mechanic, teach me about fuel injection, and strain my marriage. A dead engine has three possible culprits: electrical, fuel, or mechanical. I quickly ran electrical tests and checked to see if the timing belt was working. They were fine. I soon surmised the problem lay with the fuel system. But where? In olden times, a car used

a carburetor -- a purely mechanical device. But, automotive engineers

strove for meaning in their lives and asked us to indulge them

their creation of the fuel injection system, a cohort of electronic

and electromechanical devices. It’s like somebody re-inventing

the bicycle. Striving toward complex efficiency, they’d

monitor your oxygen and bean intake, put a cooling fan on you,

test your urine and CO2 exhaust, and mount a personal gas

propulsion component to fire the methane coming out your rear.

All more complicated in the name of progress! |

|

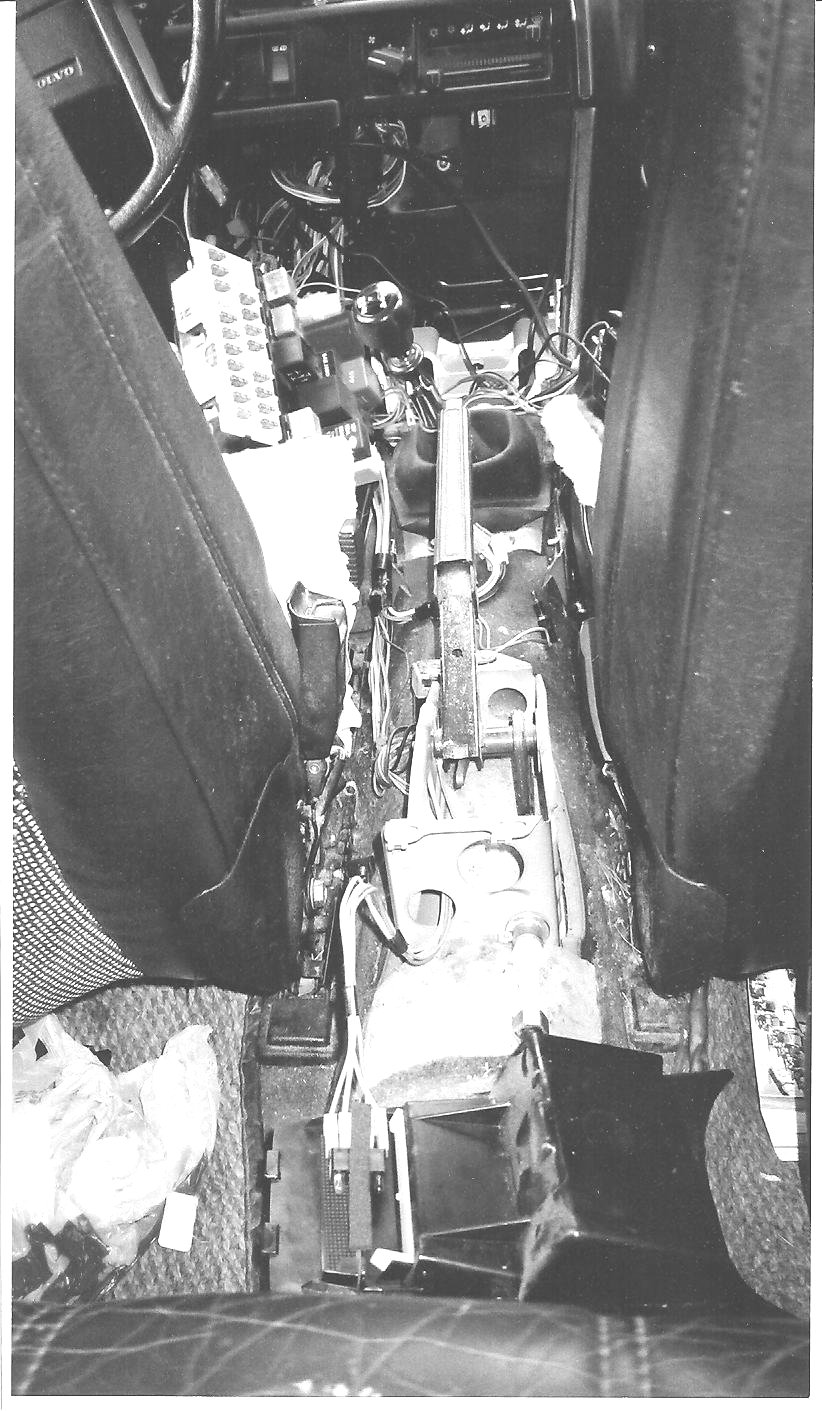

Not easy for a neophyte. One manual had the wrong colors for the wires. The other manual’s wiring diagrams looked like a fractal surface -- the closer you looked, the more complicated it got. I focused on the fuel pump relay first. But, where was it? The manuals didn’t locate the components on the car. But, sometimes technology helps solve technology. A Volvo chatroom revealed the fuel pump relay’s location. Another website displayed a wonderful wiring diagram of my system, including the relay. Wiring colors were correct and system component locations were displayed! Many suspects took center stage during the 6 ½ weeks it took to smoke out the guilty party. I encountered many dead-ends and red herrings. “How’re you doing?” my wife would ask. This is the woman who, on our first date, wondered why I drove my 1969 Volvo 122 with the windows wide open in a Connecticut winter. “It’s because I broke a stud on the exhaust manifold,” I explained. Back to the current project. “I found shorts in two separate circuits!” I said. “Imagine that!” But, the more I thought about it, that was highly unlikely. Educated as a theoretical physicist, my experimental skills were rusty. So, I called my cousin, Riley, in Hawaii. He graduated from Linfield College, in Oregon, with a Bachelor’s degree in physical science and was trained as an Army microwave technician, serving in Vietnam. He’s a hands-on type of guy. We decided the “shorts” I had found were, indeed, red herrings. As time dragged on, my wife would invariably ask, “So, what is it this week?” “Maybe it’s the relay,” I replied. Better double-check that, I thought. Having, on other occasions, bought parts to replace “suspicious” but, in the end, innocent parties, I had no intention of once again prosecuting the innocent on mere suspicion. To do so was expensive. Finally, the fuel pump relay was exculpated and the main fuel pump was found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. I made no expensive assumptions here, just the cold, hard facts as I saw them, hammered home by repeated testing. “I’ll be working with gasoline,” I told my wife, before I disassembled the main fuel pump and filter. That evening: “My God! Open the windows!” my wife yelled. “The garage smells like a refinery! And you smell!” I cleaned up as best as I could to please her. Inured to the smell of gasoline, I thought she was overreacting until I saw our Chow Chow veer toward the basement for fresh air. He rarely went there, even if bribed with dog biscuits. Now, he was running for it like a prisoner making a break for freedom -- in this case, running from the stench of gasoline that wafted through the house. My wife shunned me that night. The next day, I aired out the garage while I installed the new main fuel pump and filter. The moment of truth finally arrived. I turned the ignition key to “Start.” The engine turned over but did not run. I felt deflated. I had been so sure! All those weeks laboring in the cold, thinking and testing --- plus $220 spent on a new main fuel pump and filter. Had I misdiagnosed the problem? Goodbye, Wife! I took a deep breath. Maybe the fuel line needed to be primed. I tried again, stepping on the accelerator. The engine caught and ran like galloping horses! I smiled and relaxed. My wife smiled, too. It would take another two weeks to put the panels and trimwork back together. “You can take anything apart,” my wife said, “but can you put everything back together?” Well, not exactly. In the end, a small solenoid and bolt are still lying around. But, hey, those are minor parts. The car runs. |